Carrying children matters on many, many levels. It helps to build resilience by encouraging the formation of secure attachment relationships.

What is secure attachment?

All children form some sort of attachment relationship to their primary caregivers; there are four major types (1) of infant-parent attachment, (secure, insecure-avoidant, insecure-resistant and insecure-disorganised). Children with secure attachments have a consistent, loving relationship from which they feel able to confidently explore the world as they grow. They feel protected by their caregivers, and they know that they can depend on them to return if they leave briefly. Secure attachment is the bedrock for emotional and physical health, and for children, it is the springboard to confident independence, more positive self-esteem and better social relationships later in life.

Having a strong, reliable, trustworthy set of loving, intimate relationships allows human beings to thrive; when this is missing, problems arise that have an impact on the wider society.

What is resilience?

What is resilience?

Now this is a difficult question to answer! The word “resilience” has mushroomed over the last century, and is often mis-used, especially in mental health settings. People in crisis or enduring difficulties are often told to “be more resilient” or to “work on their resilience”, which betrays a lack of understanding of the term, and also puts pressure back onto the individual to resolve the hardship alone.

- Resilience is not about being resistant to demands, having an ability to say “no, that is not my job”.

- It is not being stoic and presenting a face to the world saying everything is fine (when it isn’t).

- Nor is resilience a rigid control or suppression of emotion, or even a lack of emotion or feeling. We are often too afraid of emotions, or the expression of our feelings… emotions are not the enemy! Emotional intelligence is a great goal to have. It helps to be aware of and able to understand, express and manage our emotions in a way that ultimately improves our relationships with other people, as well as ourselves. It is also much healthier; we need to recognise that negative emotions are not bad, but expressions of our internal landscape, and it is better to deal with them.

- Nor is resilience about independence, (we human beings do best when we are in mutually supportive relationships). It is not about not needing to ask for help, or being able to cope or function alone.

So what is it?

It may help to consider an example of a resilient ecosystem; it has an ability to absorb disturbances while retaining the same basic structure and ways of functioning. It displays the capacity for self organisation and the capacity to adapt to stress and change.

How does this fit into the context of parenting?

It really helps to consider resilience as part of how a family or community unit can adapt to the challenges of life, and continue to function effectively, providing support and love and encouragement to the individuals in this network.

In this safe and committed space, emotions can be explored, stress can be managed and eased, changing situations can be adapted to, positive (growth) mindsets can be reinforced, bereavement or disappointment or pain can all be shared within a system that focuses on those needing the most support at that time, using everyone’s different skills and abilities for the benefit of the whole.

So the lone trees above might be part of a forest that acts as a more effective windbreak, or the boat might be part of a flotilla all moored and linked together, not just relying on a single rope and anchor and a sandy floor. The ball might be one of several rolling around in an elastic net. It could be like the groups of people in the tree, all linked together and also linked and connected by wider services. A child may find a great deal of support from a nursery keyworker or a school teacher, or a grandparent, or a neighbour.

Building “resilience” to adverse life events in our family and community units will help our children to bounce back from tough situations and to thrive, despite disadvantage.

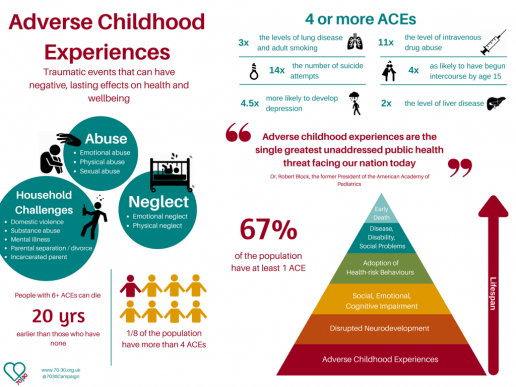

Before we move on, it will help us to consider what difficulties or disadvantages a young child might experience; a concept that is often described as “Adverse Childhood Experiences” (4).

What are Adverse Childhood Experiences?

The American CDC Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study is one of the largest investigations of childhood abuse and neglect and later-life health and well-being ever carried out. Data from 17,000 participants of a health care programme in California (questionnaires about their childhoods) was collected and the result published as ““Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults” (American Journal of Preventive Medicine; 1998, Volume 14, pages 245–258). (5)

The initial study measured ten types of childhood trauma. Five were experienced directly by the child — physical abuse, verbal abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect. Another five related to the experiences of other family members: an alcoholic parent, a family member who was a victim of domestic violence or abuse, a family member spending time in prison, a family member diagnosed with a mental illness, and the loss of a parent through divorce, death or abandonment or other circumstances.

Some examples of the questions asked were:

- Was a household member depressed or mentally ill, or did a household member attempt suicide?

- Did you often or very often feel that … no one in your family loved you or thought you were important or special? … or that… your family didn’t look out for each other, feel close to each other, or support each other?

- Did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often… push, grab, slap, or throw something at you? or… did they ever hit you so hard that you had marks or were injured?

The study found that at least two thirds of the participants had at least one adverse experience in childhood, and more than one in five reported three or more ACE’s. The study participants were mostly white, middle class college-educated Americans. The implications of how common ACE’s are in this more privileged demographic are very sobering… most of the people of the world do not have these advantages.

Later ACE studies include bullying, being part of the foster care system, being an immigrant, being homeless, living in a war zone, experiencing racism, witnessing abuse or violence outside the home and many, many others.

So, what are the effects of Adverse Childhood Experiences?

As the number of ACEs increases so does the risk for the following (this list is not exhaustive):

- Alcohol abuse

- Chronic lung disease, often related to smoking

- Diabetes

- Autoimmune disease

- Ischaemic heart disease (angina and heart attacks, heart failure)

- Liver disease (often related to alcohol or infection)

- Obesity

- Reduced quality of life due to poor health

- Depression and suicide

- Illicit drug use

- Poor work performance

- Financial stress

- Early initiation of smoking

- Smoking related ill-health

- Early initiation of sexual activity

- Unintended and teenage pregnancy

- Intra-uterine fetal death

- Sexually transmitted diseases

- Risk for sexual violence

- Poor academic achievement (6)

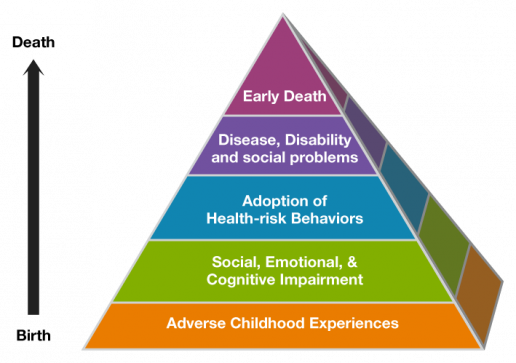

This pyramid diagram from the ACE study explains well the impact of adverse childhood experiences.

There is a strong link between the toxic stress of adverse experiences and the long term consequences. The higher the ACE score, the higher the risk of an adverse outcome. Toxic stress has a very negative effect on the development of the child’s brain; the prolonged activation of the stress-response systems disrupts neurodevelopment (how nerves grow and build connections) and cognitive function (reasoning, memory , attention, and language). (7) This leads on to developmental delay, negative health choices, and physical illness and disability such as ischaemic heart disease, liver disease and diabetes. The depression and suicide rate is massively multiplied with an ACE score of 5 or more.

This infographic from the 70/30 resource is a helpful summary.

Please note that not all stress is toxic.

Stress is a mental, physical and biochemical response to a perceived threat or demand. Toxic stress is prolonged activation of the stress response system without any buffering or protection and this has a negative effect on the growing brain.

Brief episodes of distress that are responded to in a loving fashion from a reliable, present caregiver are not toxic, and do not cause lasting harm. Some stress is beneficial and can help children to learn more about themselves and the world around them (eg the first day with a new caregiver).

“Not all stress is harmful. There are numerous opportunities in every child’s life to experience manageable stress — and with the help of supportive adults, this “positive stress” can be growth-promoting.”

More prolonged stress (such as the death of a loved one) has more of an impact, but with the right environment and loving support, children recover from this with no long-lasting damage – “tolerable stress”. (8)

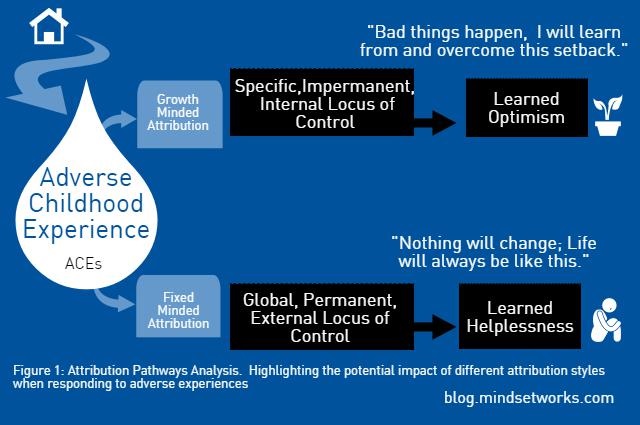

How families deal with stress matters; the mindset with which children learn to approach problems can have a very significant impact on how they perceive life events. Resilience coaches often talk about promoting learned optimism rather than learned helplessness, and supportive communities can help with this.

How can we help our children to thrive despite how common adverse experiences are?

It is clear that what happens to our children in their early years matters enormously. The Harvard Center on the Developing Child resource makes it very clear that young children “experience their world as an environment of relationships, and these relationships affect virtually all aspects of their development.” (9) It has become very obvious that those children who do thrive despite their early adversity have one thing in common; at least one stable, consistent, loving and reliable relationship with an adult (and I would add, more than one, a network of support). This is how “resilience” to the adverse events of life in this context develops; a deep seated certainty that no matter what life throws at you, you are loved and valued, and that there are people who care about what happens to you. This is what a secure attachment relationship is; a strong attachment to someone who has proven they will, most of the time, meet your needs, nurture you, love you and not let you down. Having at least one, and ideally several, of these loving and supportive relationships is what will get a family unit through the toughest of times.

It is important to remember that nobody is perfect.

What matters in building relationships is not perfection, but overall consistency. The “serve and return” theory of brain development (10) helps us understand how children learn; when an infant does something (eg smiles, or coos, or cries) and a parent responds appropriately (smiles back, coos, or picks the baby up and comforts it), a neural connection is formed. The baby has served the ball, the adult has returned it. Baby serves again, and again the same response comes back. The baby learns that their actions bring reactions; and when the overall response is similar, the connection becomes “sticky” and the baby has learned how to interact with the world and make things happen in a positive way. A framework for how to interpret the world is developing; is the world kind, or harsh? Are the caregivers present, consistent and responsive most of the time, or are they mostly inconsistent, absent or harmful?

Sometimes when a baby serves, the ball may not come back from the adult as expected… this is the “rupture and repair” theory. If the ball does not come back, this is stressful and baby begins to cry and try to encourage the adult to respond the way they have come to expect. Baby will try serving again; and if there is now an appropriate response, a briefly ruptured relationship is repaired. We do not have to be perfect, we only have to be good enough, and very often, “good enough” is actually less than we think it needs to be. This should bring reassurance to those who worry they are getting it wrong. The presence of concern and an interest in working on building positive relationship and resilience is in itself, indicative of an overall loving and nurturing situation.

How can we build resilience?

This is a really vital question, as solutions to stop the traumas from happening in the first place are better than dealing with its effects, but these solutions are hard to come by. That involves change at a societal and governmental level…

It is supportive communities of relationships that moderate and buffer against the effects of trauma, creating resilience. The first relationship a child usually experiences is that with its mother.

Building secure attachment to the primary caregivers and buffers to adversity begins very early. An infant’s brain begins to grow and develop in utero, and many antenatal care practitioners believe that building a child’s mental health in a positive way begins before birth, by caring for the mother-to-be and early recognition of potential problems with timely provision of support.

Once baby has arrived, the outside world begins to have a greater impact on physical and psychological development. This is one reason why there is so much interest in early skin to skin contact and “kangaroo care” for premature and newborn infants. There is a wealth of data showing the enormous positive effects that this early loving skin to skin contact can have on both babies and their parents, (11) reducing infection, hypothermia, severe illness, lower respiratory tract disease and overall mortality. Babies gained weight quicker, were discharged earlier and markers of mother-infant attachment were higher.

The role of soft touch in helping children cope with stress

There has been much further research into the importance of soft touch for premature babies. The medical care that these babies often need in the intensive care unit can mean they experience fewer gentle tactile stimuli and more painful procedures than other babies. Evidence is emerging that suggest that this deprivation of soft touch affects how their brains develop. (12)

The feeling of soft touch is thought to be transmitted via nerve fibres called c-afferents, taking messages from skin receptors to the brain via a slower-moving pathway than pain messages. These c-afferent fibres are believed to be linked to the stress response. Cortisol is one of the main hormones involved in the experience of stress (along with adrenaline) and prolonged exposure to high levels of cortisol is known to be damaging to the growing brain (the toxic stress we have discussed earlier).

Research seems to suggest that activating the c-afferent fibres (ie by soft touch and stroking) has an effect on particular DNA in human cells. It prevents “methylation” which in effect, switches off the glucocorticoid neurochemical receptors to cortisol in the brain. These receptors are involved in modulating stress; if they are methylated, they are switched off and not able to respond to the floods of cortisol released during stress, and cortisol continues to circulate, c

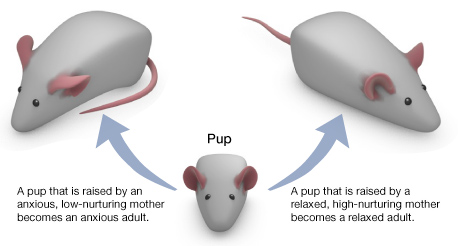

These DNA changes are passed on to the next generation. (13) This has been demonstrated in mouse pups; mouse pups that are highly licked and groomed by their parents grow up to be relaxed adults who are high lickers and groomers of their own offspring; and mouse pups who are brushed rather than licked by a parent become high licking and grooming parents themselves. (14).

Clearly, soft touch affects infants’ brains, their sense of self, and how they grow up. Soft touch matters; and holding babies and being in close contact with them provides this frequent, consistent loving soft touch.

Mindset matters

Mindset matters

Helping children to respond to adverse events in a “growth minded” manner will also help them to build resilience. This is where the supportive adults around them can help them learn to process events and to grow, rather than become helpless in the face of a perceived lack of control. We may not be able to change what has happened but we can control how we respond to it. (I am not suggesting that there needs to be a relentless immediate positive response to every event; emotions are best explored and processed at appropriate times!)

Carrying Matters

There is little doubt that holding babies, providing loving close contact with them, creating relationships where problems can be discussed and shared is of huge importance on many levels, to babies, their carers, and the wider society. Holding, carrying, hugging, interacting, these all build the social brain and show children that the supportive networks around them are their safety net and their buttresses. However, holding growing babies is hard work, we don’t tend to encourage them to use their inbuilt gripping reflexes to make it easier for us. The pace of modern life and expectations or misconceptions often make us put our babies down; we hold and carry them in arms them far less than they really need.

This is where a sling or carrier (I use the word interchangeably) can become very useful!

Here are some of the ways in which carrying children in slings can help build secure attachment relationships and thus help to develop emotional intelligence and “resilience”.

- Connection; carrying a child often builds a feeling of being connected to another human being. The familiarity of being carried close helps to create secure attachment. It is relationship that builds a sense of belonging to a supportive network, that creates this “resilience”, and the gentle touch and closeness stimulate oxytocin release, the hormone of bonding. It is also a safe space that allows (with older children) to discuss and process difficult situations and learn to deal with them positively, encouraging a growth mindset.

- Safety; a child who is settled in a well fitting carrier will feel safely contained, which can be very helpful when they are feeling overwhelmed or distressed. Being close to a loved one is calming, as is the rhythmic motion of carrying. Many children find the feeling of an all over hug relaxing and reassuring (less so when they are feeling active and wanting to explore!)

- Emotional regulation. Studies seem to suggest that babies cry up to 43% less in a carrier, and this is in part due to the close contact, the containment, the gentle movement and the feeling of having been responded to. Big feelings can be easier to cope with from a position of security, and children will calm down when they feel safe. In a sling, they are less likely to be immediately put down, which then gives the opportunity for relationships of trust to deepen. Furthermore, if a child stops crying when they are carried, a parent may feel more confident in their ability to soothe their infant’s distress. This will encourages a more loving response the next time baby cries and relationships will strengthen, building the family “ecosystem” into a more resilient one. Children can help heal their parents too with their love and their joy, it is not a one-way relationship!

- Reducing the stress response; soft touch and stroking play a role in reducing the effects of the stress response and increasing oxytocin. The parasympathetic system is activated, and as we have seen, less stress is good for the growing brain, so using a carrier helps babies to be less stressed (and parents too). They will often fall asleep when they feel calm and safe, in a trusted place, close to their carer.

- Reconnecting after time apart; Having a familiar carrier and being held close can be very helpful for children to reconnect with their parents or primary carers after a day at nursery or with another carer they may not know as well. The familiarity and consistency helps them to build an inner confidence that these key relationships are still intact. Many childminders and nurseries are beginning to use slings as part of their daily routine!

- Encouraging conversation; children who are held close to their parents are exposed to plenty of conversation and social interaction, which helps them to build a sense of their place in the world, the things in it and how to engage with it. Loving interaction helps brains to grow.

- Spending time together; using a carrier for a child as a parent goes about their daily life means that children still feel close even if they are not the primary focus of attention. This encourages relationships to develop in the background!

- Building inner self esteem; children who feel close to their parents and have their needs consistently responded to, are building a sense being worthy of love and attention. This belief that they are loved and that they matter to someone will build a more secure foundation for the future.

- Better sleep; children who get plenty of sleep (and most babies love to sleep where they feel safe; on arms or a sling) are more able to handle changes to their routines or stressful situations.

- Wider circle of primary carers: being carried regularly by several carers helps children to build more positive, trusting relationships with more people, which can lessen the burden on the parents.

- Transition: a sling that has been used in hospital for a premature baby and then comes home with the family can really help with adjusting to a new environment. The parent’s body is still the baby’s primary safe place, no matter where they are, and the scent and feel of the familiar sling will provide reassurance.

- Building bridges with adoptive/foster parents: a sling that is familiar and comfortable and travels with the child can help with the transition of care from one carer to another.

Summary

Children need loving nurture in the early weeks and months of their lives, and long beyond this for normal, healthy development. Carrying babies close to an adult’s body, as human beings have evolved to do, is vital for normal physiological and psychological development. Research into the importance of skin to skin contact, soft touch and responsive parenting, as well as a better understanding of disability reinforces this.

The presence of a reliable, consistent, loving relationship with a primary caregiver and a wider network builds resilience in the sense we have discussed here. It enables children to thrive despite early adversity. Using a sling can help to build these vital relationships and forge strong, protective, secure family bonds. We should all carry our children often, despite Western society’s mistaken focus on “early independence” and telling parents to put their babies down.

This attitude seems to be creating more problems for our children as they grow up; we need to invest much more in providing support to parents and their children in the first five years of their lives, rather than only focusing on dealing with adult ill health, much of which could have been prevented by timely intervention in their childhoods.

Children are often great healers too, with their simple approaches to life and their ways of seeing the world. Their loving, responsive touch affects their caregiver’s biochemistry too and can have a positive effect on a parents’ low mood. A functioning, resilient family unit, supported by an elastic safety net of a committed, available community is one that can adapt to change together, support each other, build each other up, creating a sense of control over their lives rather than helplessness.

Carry your babies! You are investing in their futures, as well as your own.

Further Reading

70/30 resource, aiming to reduce child maltreatment by 70% by 2030

Unicef and health child growth

What is resilience?

What is resilience?

Mindset matters

Mindset matters