The prevalence of Perinatal Mood Disorders (pre and post-natal depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder) is increasing in Western society as it is increasingly fractured and isolated, with a decreased sense of local community and shared care. The birth of a baby is often an overwhelming time for both parents, especially when also faced with the expectations and demands of a fast-paced culture that often judges people by their apparent productivity and appearance. As a GP, I see many families struggling with these conditions that are often diagnosed, and keeping babies close may play a part in surviving these illness, mainly due to the closeness with your child, rather than the choice of sling.

Postnatal depression is on the rise – affecting at least 10-15% of new mothers (with many more sufferers (and fathers) never being recognised to have the condition). Anxiety and PTSD are also worryingly common. Parents are encouraged to put their babies down as much as possible and regain their old lives; babies are expected to learn independence as quickly as possible and stop relying on their parents for their every need.

This approach to caring for children is very new in human history and runs counter to attachment theory, which suggests that the human infant thrives on responsive parenting and close contact.

Read about Ruth’s experience of antenatal depression here; for the rest of this post we will focus mainly on postnatal depression (PND).

What is Postnatal Depression?

Postnatal Depression is a depressive illness which affects between 10 to 15% of new mothers. Many more are never diagnosed with this condition, which can become a very significant issue in the functioning of a family. It is often poorly managed by health care providers, and can be misunderstood by the community and dismissed as “just the baby blues” or “tiredness.” It is common for sufferers to feel very alone and unable to explain just how they feel and why it is so difficult to endure. Prenatal depression is also experienced by many new parents, and postnatal anxiety and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder are also commonly experienced pre and postnatally.

Why is it so common?

Western society is increasingly fractured and isolated, with a decreased sense of local community and shared care. Depression is common in our culture, for reasons not clearly understood, but partly due to the way we live. The birth of a baby is often an overwhelming time for both parents, especially when also faced with the expectations and demands of a fast-paced culture that often judges people by their apparent productivity and appearance.

Before parenthood, people’s identities are often based on their roles and responsibilities in life; work, friendship circles, hobbies and interests. After a baby arrives, this often changes dramatically, sometimes in unexpected ways, and for many, the huge change in the pace of life and the loss of control can be very difficult to deal with. “The burden of conscious responsibility with no let up and the unusual and unexpected degree of fatigue can make a mother feel desperate about whether she can survive and how she will manage.” (Kennell & Klaus) This is the role that community used to play; supporting and carrying each other’s burdens as part of a committed and close-knit group of people who lived together, an experience that few parents enjoy in the West today.

What does it feel like?

Common words used to describe PND are guilt and inadequacy.

“The worst part was the guilt I felt about crying every day when I had a beautiful new daughter.”

“It isn’t about not loving your baby but about feeling overwhelmed with responsibility and unable to cope.”

“My head can feel empty and I have no thoughts.”

“It is just so hard to face another day of feeling totally unlike myself, missing my old life, unable to enjoy this new one.”

Fathers suffer from depression after birth too.

“The first few weeks were the hardest and I would just sit and cry. I felt like this shouldn’t happen to me, I should just be taking it on the chin and getting on with it. But the truth is, I felt alone and without the support of my wife, I would’ve been a lot worse.”

Many parents with PND feel a sense of dissociation and detachment from the child they want to love so much.

“It isn’t about not loving your baby but about feeling overwhelmed with responsibility and unable to cope.”

Caring for people with PND is hard.

“PND is the scariest and loneliest place on the planet and puts a terrible strain on the whole family.”

“My husband felt helpless because he knew something was wrong but I wouldn’t admit it and shut him out. All he could do was try to look after me and be there when I finally admitted it. It caused a lot of irrational arguments.”

What can I do?

If you are suffering, or think you may be suffering from perinatal mood disorders, first be reassured that you are not alone and the vast majority of people with it survive with few long-term ill effects.

Here are some suggestions that may help.

Get help where you are.

Tell your nearest and dearest how you really feel.

“I found the hardest bit was to admit that I wasn’t coping, even when it looked like I was, I was fine on the outside but was a complete mess on the inside.”

Many women testify how supportive their partners and families and close friends are once they understand – ask them to help with the basic jobs of daily life; cooking, cleaning etc. Help them to see how useful you will find it when they listen to you with acceptance and without judgement, and how their understanding when things go wrong is vital. Guilt is a large part of PND and many kind people may inadvertently add to this burden.

Get help from your local health care providers.

This may be your GP, your midwife, your health visitor, your local SureStart centre. The quality of care from these resources can vary enormously. It can help to write down on paper how you feel in advance and what you think you need (validation, formal counselling, CBT or medication, for example) and take it with you to appointments. Continuity of care is great, if available; a HCP who listens and cares can make a greater difference than one who fires questions and is keen to tick boxes and prescribe medication at once.

“Guilt and lack of confidence are so typical of PND and my HCP was essentially validating those feelings even though objectively I was doing a great job!”

Be armed with information (e.g. if you wish to carry breastfeeding, sertraline is safe in these circumstances). The Breastfeeding Network is a valuable resource. If you are not satisfied with the care you are receiving, find different care.

Get help from your local non-NHS resources.

These can be very useful, such as HomeStart (a befriending service) and local PND groups. A postnatal doula may help, and there are many national helplines and resources (see below)

Get help from online social resources.

There are many forums and parenting groups full of people who know how you feel, and will listen and share. Being among people with the same values and parenting beliefs may be a source of great encouragement. Equally, avoid too much time online.

Get out!

It can be very hard to actually get out of the house when struggling with dark thoughts or hopelessness, but it is worth the effort involved. Even a walk down the road is a good start, and encourages release of endorphins (the natural feel-good hormone). Arrange to meet some friends, and ask them to encourage you to come. Try to make a plan for most days, and be kind to yourself if you decide on a pyjama day instead. Try to arrange some time to spend alone with your other half, to remember who you still are, as well as parents.

Get nourishment.

Good quality food, drink, exercise and sleep are vital to your own health and sanity, as are times to enjoy the things you used to. Dress well in bright mood-enhancing colours. You are still a person and your own needs should be met as much as your child’s. Some people make use of night-time carers to allow some much-needed uninterrupted sleep.

Get past your birth story.

For many women, recovering from birth takes a while, especially if it was not the hoped-for experience. The NHS Afterthoughts service and counselling can help if you feel a sense of grief.

Get a sling or carrier.

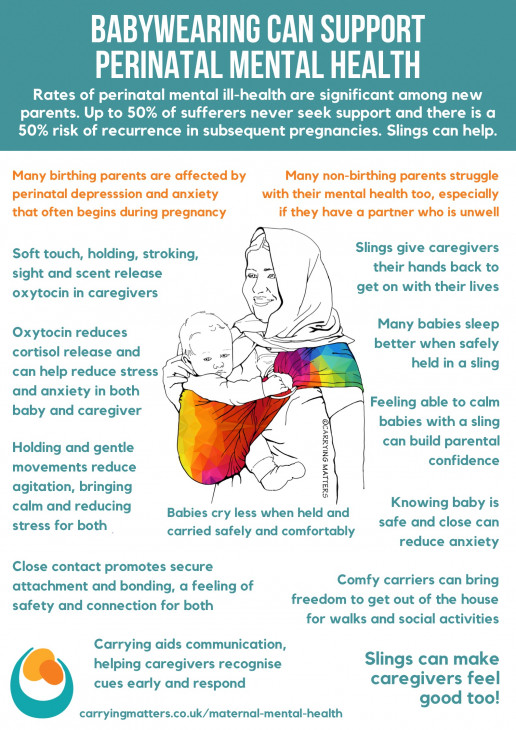

Keeping your baby physically close is well known to stimulate the release of oxytocin. Oxytocin is a hormone that is closely related to bonding and attachment. It is released during labour and breastfeeding, and, crucially, during skin-to-skin contact and social interaction. It has an important role in encouraging nurturing feelings and a sense of belonging, and reduces anxiety and depression by affecting cortisol release.

Babies who are in close contact with their parents have been shown to have a corresponding higher level of oxytocin than their non-carried counterparts; which subsequently helps to reduce baby’s own stress levels and improve their sense of secure attachment; their needs are met at the point of request. Calmer babies are easier to care for; win/win.

The soft touch of close skin to skin contact reduces the release of cortisol, the stress hormone, via C afferet fibres affecting receptors in the hypothalamic-pituitary-axis. Stroking has been shown to reduce pain responses.

Modern life is fast-paced and for many, constant carrying of ever-growing children can be difficult to achieve, or uncomfortable after the travails of birth. This is where the practice of using a sling, (sometimes known as babywearing) can be of great value. A soft sling that allows you to keep your child close to you, (thereby stimulating the release of oxytocin and reducing cortisol), and helps your baby to relax and sleep in secure comfort may make a huge difference to your life and your feelings and help you to feel that you can cope. Anxiety may settle a little as you know your little one is safe next to you.

“The sling brought us back to an almost pregnant-like state, with him a part of me, listening to one another’s cues. He was calmer for being close to me, which made me feel more confident, which brightened my mood. Leaving the house felt less daunting so I got more exercise and again increased my confidence. I talked to him more, whether he was awake or not, and he became my son rather than a tiny scary stranger.”

“My favourite thing in the whole world, that never fails to calm me or lift my mood has been cuddles with my baby, particularly skin-to-skin. For me, there is no antidepressant like it.”

“When she was in her pram I felt completely removed from her and her world. I was just an accessory, she was a job to do and I was irrelevant. Using a sling finally helped me bond properly with her and made a massive difference to the PND.”

Many slings are extremely comfortable to use, and can be very practical indeed. It is possible to learn how to feed discreetly in a sling, allowing you more flexibility about being out of the house for the day with your baby.

Slings give you and your baby the freedom to be on the move together, rather than feeling stuck; to go out into the world for a walk or go shopping without struggling with the complexities of a pram. Movement and exercise are vital to wellbeing; and using a sling safely can help your body recover from birth and become stronger.

Slings can be beautiful and colour therapy can help to lift the mood. Learning a new skill can be therapeutic, and many parents find a great sense of community among other sling users both locally and online. This can help with feelings of isolation, especially if you have chosen to parent differently from your family or your peers.

Get a sense of perspective.

What matters in these early months is you and your baby. It does not matter what other people think; the house does not need to be pristine, you do not need to impress people with how well you are taking to parenthood. I have heard many women describe how they “are falling apart on the inside”.

“I thought because I wasn’t suicidal or not looking after things that it couldn’t be PND so held back for a long time from accepting it and getting help.”

“I found the hardest bit was to admit that I wasn’t coping, even when it looked like I was, I looked fine on the outside but was a complete mess on the inside.”

Get confident again.

Reflect on what you have achieved so far and use that to build self-belief. Learn to trust yourself, be an instinctive parent – and you will fin that as you encourage others, you will find yourself lifted too. Some people find going back to work can be very helpful; the chance to use skills again and have adult interactions once more can be a great boost to self-confidence.

Useful Resources

Postnatal Depression Information Leaflet

Postnatal Depression Information Leaflet 2

Pre and Postnatal Depression Advice and Support (PANDAS)

Mothers for Mothers Postnatal Depression Support

Postnatal Illness Information (PNI)

The Impact of Babywearing on Mothers’ Mental Health – Aimee Gourlay

Further Reading

“I carry my heart in a sling” – a blog on how slings helped Lindsay fight her PND.

Sling Sally’s talk on Slings and Sanity for the 2015 Northern Sling Exhibition

Surviving PostNatal Depression – Selina Shaik for MIND

How Carrying Helped My Recovery – Ellie at Peekaboo Slings

Carrying With A Mental Health Disorder – Andrea’s story